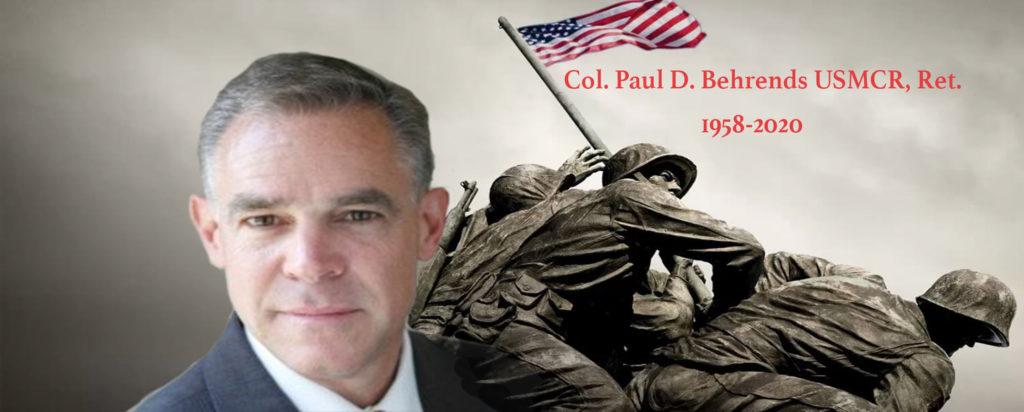

We lost an extraordinary friend and ally: Paul Behrends, 1958-2020

In another age and place, Paul Behrends would have been straight out of Rudyard Kipling.

The extraordinary life of the retired US Marine Corps reserve colonel and longtime congressional staffer ended December 12 when Paul died from injuries near his home in Sterling, Virginia. He was 62.

God and country. That, with his family, summed up Paul’s life. As a young active-duty Marine Reconnaissance officer in the 1980s, Paul parachuted into Afghanistan as part of the Reagan administration’s spectacular covert operation to assist resistance fighters against the Soviet invader army.

From there, as a civilian, Paul went to Central America to help defeat the Communist insurgency in El Salvador and the Soviet-backed Sandinista regime in Nicaragua. Having spent so much time in the field, he was shocked to see how an influential few on Capitol Hill and in journalism supported the Communist enemy.

It was working the Central America front that Paul understood the blood sport of Washington politics.

Not an establishment fixture

While others in Washington stayed comfortable in the 1980s by simply writing about the Soviet threat, Paul inspected the situation directly. During Communist martial law in Poland, Paul infiltrated the country for an on-the-ground view of the situation by posing as an American student at the University of Krakow. Some say he ran secret reconnaissance missions inside the Soviet Union.

Those and other activities gave him a unique perspective: The Soviet empire was fragile and vulnerable to outside pressures that would cause it to collapse.

Paul horrified the comfortable political elites by working with freedom fighters within the Soviet empire and inside the USSR itself to play a support role in what the political mainstream dreaded: Dismantling the Soviet Union.

Many dismissed and derided his efforts. Too unrealistic and dangerous, they said.

He succeeded.

Working in the Balkans in the early 1990s, he warned of an impending war in the region and genocide in Bosnia.

He was right.

Paul Behrends knew from his time on the ground in Soviet-occupied Afghanistan that the Islamist forces backed by Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, and Iran would one day turn against the United States.

When the George W. Bush presidential transition team interviewed him in 2000 to serve as assistant secretary of state for Asia, Paul was asked his views about the greatest immediate threat in the region.

Instead of giving a packaged establishmentarian India-versus-China answer that would have clinched the senior policymaking position, he said that the greatest immediate danger came from a terrorist group based in Afghanistan and Pakistan. The terrorist movement, he said, called itself al Qaeda, headed by a Saudi fanatic named Osama bin Laden. The Bush State Department interviewer had never heard of either, Paul was asked no further questions, and someone else got the job.

Accomplish anything if you don’t care who gets the credit

Paul’s unusual global network of unusual people included the types of characters that few Washington careerists would dare venture to meet, let alone get to know.

He didn’t network to self-promote in a town whose currency is self-promotion. His unconventional worldview was as unconventional as the people he befriended – people whose views often had little or nothing in common with his own.

While the conventionally minded expended their energies running the hamster wheel of Washington, Paul took the road less traveled. He was on a first-name basis with the Speaker of the House, at one point, running interference for him while working loyally for a congressman whom he knew would never become a real power broker.

That’s because Paul never sought to become one. He wasn’t a soulless broker. He was a doer.

And as he had learned from Ronald Reagan, he could do anything as long as he didn’t care who took the credit. And the credit, he knew, would often go to the self-promoters. Or, more positively, he would let it pass to his friends and others he admired and wanted to elevate.

Unconventional friendships and solutions

In the crucial days following the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks, President George W. Bush was faced with what seemed like an impossible task: Launch an invasion of a remote, land-locked, primitive country in a forbidding and often hostile region.

Paul had a key part of the solution. He tapped his old Afghan commander relationships to arrange for the Uzbek and Tajik anti-Islamist leaders of the Northern Alliance to welcome the first US special operations forces into Afghanistan – many on horseback – to commence the long hunt to destroy al Qaeda and eliminate Osama bin Laden.

But his previous Afghan work was against the Soviets and the Communist regime in Kabul. A key Afghan leader against the Taliban, General Abdul Rashid Dostum of the Uzbek tribe, had been on the Soviet side fighting Paul’s old friends in the resistance. It was Paul’s ability to work these rivalries and understand tribal politics and cultures that helped General Dostum become a key ally of the United States and start the war against al Qaeda. Paul remained friends with Dostum until the day he died.

Paul was part of a private initiative in Nigeria that successfully kept Boko Haram terrorists from operating in at least 10 Nigerian cities. He tried to get the Obama administration to build a strategic relationship with Nigeria to defeat Boko Haram while it was still small – letting Obama take the credit – but the administration was unwilling. Soon after, Boko Haram kidnapped hundreds of girls and held them hostage – an atrocity that might never have happened had the administration taken his advice.

Congress, Blackwater, and the Knights of Malta

A well-known professional staff member in the US House of Representatives, Paul worked for years for Congressman Dana Rohrabacher (R-Cal.), and on the House Foreign Affairs Committee, where he was staff director of the Eurasia subcommittee.

He briefly served in the private sector in association with Blackwater USA, founded by his former intern, Erik Prince.

Paul’s Catholic faith and his deep concern for human rights and humanitarian relief motivated him to become a knight in the Sovereign Order of Malta. He was a board member or active member of charities and humanitarian organizations.

Networked with everyone

Paul Behrends was a quiet and cheerful networker who met with literally anyone, friend or foe, who sought him out. His shallow-minded critics would later use those relations against him, to attack his reputation and cause people to question his motives.

Paul wasn’t deterred. A student of German history, he knew the value of reconciliation after grueling conflict and appreciated the tough decisions, as after World War II, to let some of the bad guys get away in order to build the peace. His early experience with Afghan warlords against the Soviets taught him that every personal contact could serve a useful future purpose.

He believed that the US should change its approach toward Russia to move beyond the Cold War and work with Russia against the far greater mutual threat of Communist China.

Influential American supporters of the Chinese Communist Party began a whispering campaign to imply that Paul had ulterior, even treasonous, motives.

Paul would often note with a smile that many of the same people who falsely called him a Putin fan were open promoters of policies that helped Beijing.

A strong friend and supporter of Taiwan, independent Hong Kong, and the Uighurs and persecuted Christians in China, he nevertheless met with Chinese Communist officials without compromising his principles.

He received or sought out seemingly everyone from Central Asian tribal chieftains to Russian oligarchs, to chiefs of state, acting always in the interests of the United States.

Known by his enemies

Some of his differences in opinion from the easy bipartisan consensus damaged him professionally.

Paul upset friends and adversaries with his principled opposition to the political operations of Bill Browder, grandson of a founder of the Communist Party USA. Browder had made himself into a political “good guy” in Washington to sanction Russian oligarchs and officials. Paul said that he objected to Browder out of principle for having capitalized on his family’s treasonous Communist pedigree as agents of Stalin in order to make what Paul described dirty business deals with Russian gangster-bureaucrats.

What offended Paul the most was that Browder had renounced his American citizenship in order to get rich in the post-Soviet gold rush, betraying his country once again. And then Browder, by choice a foreigner now, had the nerve to go to Capitol Hill to shape American foreign policy.

Browder had made a fortune under Putin and was fine with the Russian dictator until such time that he was not. That rubbed Paul the wrong way.

As Paul saw it, Browder’s use of his murdered accountant Sergei Magnitsky was not principled opposition to the Kremlin.

Paul viewed Browder’s lobbying for the Magnitsky Act as a foreign anti-American operative’s exploitation of American law to drag the United States into Russian internal gang wars under the false flag of human rights.

To some of the Magnitsky Act’s champions, criticism of Browder was tantamount to supporting Putin. So they tarred Paul accordingly. He was offered incentives to back down, but he refused.

On top of that, Paul’s work in Congress to combat the corrupting effects of globalism and George Soros networks on American strategy and diplomacy made Paul, in the eyes of the Swamp and progressivists, a serial political criminal.

That was not how a Johns Hopkins- and Harvard-educated member of the Washington policymaking community should behave.

Paul countered that none of his critics put America first. Unlike many in Washington, including certain of his accusers, he never sought to profit from his Russian, Chinese Communist, or other disreputable connections.

He never publicly defended himself against those attacks and discouraged his friends from doing so on his behalf.

Survived by a large, devoted family

Paul Behrends is survived by his children, Paul E. Behrends II, Grace M. M. Behrends, Josef S. Behrends, and Maria K. J. Behrends, whom this writer has known since they were born.

He is also survived by his mother, Kathryn Louise Behrends (nee Meiners), brothers and sisters Carol Frese (Gregory), Stephen (Deborah), Judy Witt (Dexter), Joan Van Pelt (Richard), and a large extended family.

A native of Cincinnati, Paul received his education at Xavier University, Johns Hopkins University, and Harvard University.

His biggest family is the Marines. Paul retired as a colonel in the US Marine Corps reserves.

Funeral services on December 19

A wake, or visitation, for Paul Behrends was held at his home parish on Saturday, December 19, at Our Lady of Hope Catholic Church, in Potomac Falls, Virginia.

A Catholic requiem Mass for Paul will take place at a date to be determined, followed by Military Funeral Honors with Escort and interment at his final resting place at Arlington National Cemetery.

- Chinese spies ‘sham marriage’ scandal exposes ‘targeted’ national security threat at major US base: Waller - January 27, 2026

- The “Donroe Doctrine” In Action - January 7, 2026

- Is Cuba Ready to Fall? - January 7, 2026